The mysterious death of the Somerton Man

- Paige Phillips

- Sep 5, 2019

- 8 min read

The body of an unidentified man was found at 6:30am on 1st December 1948 on Somerton Park Beach in South Australia. Since the identity of the man was never confirmed, he was referred to as “The Somerton Man”. How his body got there, and the circumstances behind the man’s death have never been confirmed.

At 6:30am on 1st December 1948, the police were contacted after the body of a man had been found on Somerton Beach near Glenelg, South Australia. The man was found lying in the sand across from the Crippled Children’s home.

His body was positioned so that he was lying with his head resting against the seawall, with his legs extended and his feet crossed. An unlit cigarette was on the right collar of his coat.

In his pockets he has an unused second-class rail ticket from Adelaide to Henley beach, a bus ticket from the city that could not be proved to have been used, a narrow aluminium American comb, a half-empty packet of juicy fruit chewing gum, an Army Club cigarette packet containing seven cigarettes of a different brand and a quarter full box of Byrant and May matches.

After the news of the discovery broke, several witnesses came forward to state that on the evening of the 30th November, they had seen an individual who resembled the man lying on his back in the same spot and position where the Somerton man was later found. A couple who claimed to have saw him at 7pm noted that they saw him extend his right arm to its fullest extent and then drop it limply. Another couple who saw him from 7:30pm to 8pm recounted that they did not see him move during the half an hour he was in view, although they did recall that his position had changed. They thought it was abnormal he wasn’t reacting to the mosquitos that were present in the air around the beach, but believed the man was either drunk or asleep and so didn’t investigate further. One witness claimed to police that she had watched a man looking down at the sleeping man from the top of the steps at the beach.

11 years after the discovery of the body, another witness would come forward and report to police that he and three others has seen a well-dressed man carrying another man on his shoulders along Somerton Beach the night before the body was found.

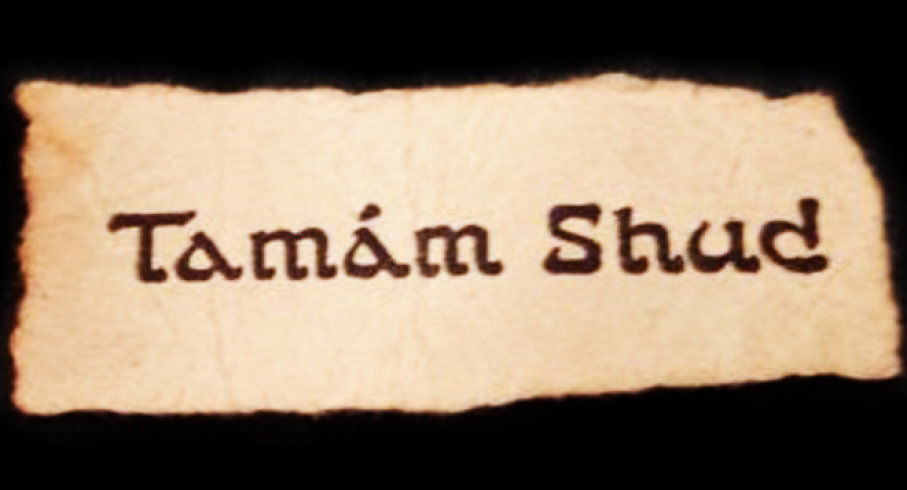

In 1949 during the inquest into the Somerton man’s death, a tiny piece of rolled-up paper with the words “Tamam Shud” printed on it was found in a fob pocket sewn within the man’s trouser pockets. The phrase means “ended” or “finished” and is found on the last page of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. The paper’s verso side was blank.

A search was conducted throughout Australia to find a copy of the book that matched the torn-out page. A man, referred to by the pseudonym “Ronal Francis” found the copy of the Rubaiyat which matched the piece of paper. It was a 1941 edition of Edward Fitzgerald’s 1859 translation of the Rubaiyat, published by Whitcombe and Tombins in Christchurch, New Zealand. On the inside back cover of the book, there were indentations from handwriting. These included a telephone number, an unidentified number and a text that resembled an encrypted message. According to statements given to the police, the book was found in the rear footwell of a car, at about the same time the body of the Somerton Man was found.

The theme of the Rubaiyat is that one should live life to the fullest and have no regrets when it ends.

The handwriting in the back of the book was considered to be some sort of code. The second line had been struck out, suggesting an error in encryption. Code experts were called in at the time to decipher the lines but were unable to do so.

The telephone number in the back of the book belonged to a nurse named Jessica Ellen “Jo” Thomson, who was born in Jessie Harkness in Mackerville, Sydney, but at the time lived in Glenelg, around 400 metres north of where the body was found. When she was interviewed by the police, Thomson said that she did not know the dead man or why he would have her phone number or choose to visit the suberb on the night of his death. She did reveal that in late 1948, an unidentified man had attempted to visit her and asked a next-door neighbour about her. The police interviewer commented that Thomson was evasive and he believed she knew more than she was letting on. In 2014, Thomson’s daughter Kate explained in an interview for 60 minutes that she also believed her mother knew the identity of the Somerton Man.

The plaster cast bust of the Somerton Man was shown to Thomson in order to determine if she could identify the identity of the man. According to the Detective Sergeant, Thomson claimed she could not identify the person depicted, but described her reaction as “completely taken aback, to the point of giving the appearance she was about to faint”. The technician who made the cast was also present when Thomson viewed it, and commented that after looking at the bust, Thomson immediately looked away and would not look at it again.

Thomson also stated that whilst she was working at Royal North Shore Hospital in Sydney during World War 2, she owned her own copy of the Rubaiyat. She stated that in 1945, she had given it to an army lieutenant named Alf Boxall. His copy of the Rubaiyat was later obtained and noted to be perfectly in-tact.

Autopsy

The autopsy was conducted by pathologist John Burton Cleland, who described the man as of having a “Britisher” appearance and believed to be aged between 40-45. He was in top physical condition, being 5ft 11in tall with grey eyes and fair to ginger-coloured hair that was grey around the temples. The man had broad shoulders and a narrow waist. His hands and nails showed no signs of manual labour, whilst his big and little toes met in a wedge shape, consistent with those of a dancer or someone who wore boots with pointed toes, as well as having pronounced high calf muscles consistent with people who regularly wore boots or shoes with high heels or performed ballet.

He was dressed in a white shirt with a red, white and blue tie; brown trousers; socks and shoes; a brown knitted pullover and a fashionable grey and brown double-breasted jacket, thought to be of American tailoring. All the labels on his clothes had been removed, and he had no hat or wallet, which was unusual for a man in 1948. He was clean-shaven and carried no ID, which led the police to believe it may have been suicide. His dental records were not able to be matched to any known person.

The time of death was estimated to be around 2am on 1st December. The autopsy showed that the man’s last meal was a pasty eaten three to four hours before death. Testing conducted failed to identify any foreign substance in the body. However, poisoning remained a prime suspicion. As there was no evidence of vomiting or convulsions at the scene, it was theorised that the man’s body had been moved after his death.

The body was embalmed on 10th December 1948 after police were unable to gain a positive identification.

Discovery of a suitcase:

On 14th January 1949, staff at the Adelaide railway station discovered a brown suitcase with its label removed which had been checked into the station cloakroom after 11am on 30th November 1948. It was believed that the suitcase was owned by the Somerton Man.

Inside the case were a red checked dressing gown; a size 7, red felt pair of slippers; 4 pairs of underwear; pyjamas; shaving items; a light brown pair of trousers with sand in the cuffs; an electricians screwdriver; a table knife cut down into a short, sharp instrument; a pair of scissors with sharpened points; a small square of zinc thought to be a protective sheath for the knife and scissors and a stencilling brush, which would typically be used by third officers on merchant ships for drawing cargo.

Also, in the suitcase was a thread card of Barbour brand orange waxed thread which was not available in Australia. It appeared to be the same thread that was used to repair the lining in a pocket of the trousers the Somerton Man was wearing.

Despite all labels being removed from the man’s clothes, the police found the name “T.Keane” on a tie, “Keane” on a laundry bag and “Kean” without the E on a waistcoat. Three dry cleaning marks (1171/7, 4393/7 and 3053/7) were also found on the waistcoat. Police believed that whoever removed the clothing tags either overlooked these three items or purposely left them, knowing they were not the man’s real name.

Searches concluded that there was no T. Keane missing in any English-speaking country and nothing came back from a nationwide search of dry-cleaning marks. The only information the suitcase provided was that the stitching in the coat indicated that it had been made in the United States. As the coat had not been imported, it revealed that the man had been to the United States or that it had been bought from someone of a similar size who had been.

Inquest into the death

An inquest into the Somerton man’s death was conducted by Thomas Erskine Cleland on 17th June 1949. John Burton Cleland re-examined the body and made a number of discoveries that had been initially overlooked. Cleland noted that the man’s shoes were remarkably clean and appeared to have been recently polished, rather than being in the state expected of the shoes of a man who had apparently been wandering around Glenelg all day.

A professor of physiology and pharmacology testified in court that a group of drugs, identified as digitalis and oubain, were extremely toxic in a relatively small oral capacity that would be extremely difficult if not impossible to identify even if it had been suspected in the first instance.

Burial

In 1949, the body of the unknown man was buried in Adelaide’s West Terrace Cemetery, where the Salvation Army conducted the service. Years after the burial, flowers began appearing at the grave. Police questioned a woman who was seen leaving the cemetery, but she claimed to know nothing of the man.

Abott Investigation

In March 2009, a University of Adelaide team led by Professor Derek Abott began an attempt to solve the case through cracking the code at the back of the Rubiyait and proposing to exhume the body to test for DNA. Maciej Henneberg, professor of anatomy at the University of Adelaid, examined images of the Somerton man’s ears and found that his cymba (upper ear hollow) is larger than his cavum (lower ear hollow), a feature possessed by only 1-2% of the Caucasian population. In May 2009, Derek Abott consulted with dental experts who concluded that the unknown man also had hypodontia (a rare genetic disorder) or both lateral incisors, a feature present in only 2% of the general population. In June 2010, Abott obtained a photograph of Jessica Thomson’s eldest son Robin, which clearly showed that he also had a larger cymba than cavum but also hypodontia. The chance that this was a coincidence has been estimated to be between 1 in 10 million and 1 in 20 million.

Since 2018, further testing has been conducted, however the identity of the Somerton Man is still unknown.

Comments